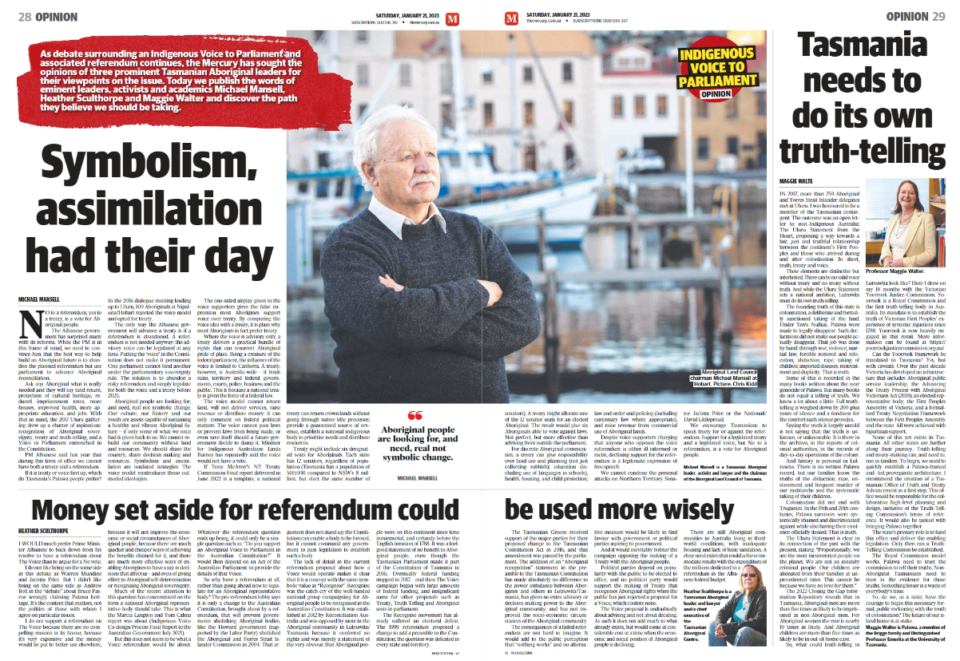

Opinion pieces written by Michael Mansell, Heather Sculthorpe and Maggie Walter on Voice, Treaty, Truth

Published in The Mercury on Saturday, 21 January 2023

Symbolism, Assimilation Had Their Day

By Michael Mansell

NO to a referendum, yes to a treaty, is a vote for Aboriginal people.

The Albanese government has surprised many with its reforms. While the PM is in this frame of mind, we need to convince him that the best way to help build an Aboriginal future is to abandon the planned referendum but use parliament to advance Aboriginal reconciliation.

Ask any Aboriginal what is really needed and they will say land return, protection of cultural heritage, reduced imprisonment rates, more houses, improved health, more appropriate education, and jobs. With that in mind, the 2017 Uluru gathering drew up a charter of aspirations: recognition of Aboriginal sovereignty, treaty and truth-telling, and a Voice to Parliament entrenched in the Constitution.

PM Albanese said last year that during this term of office we cannot have both a treaty and a referendum.

If it is treaty or voice first up, which do Tasmania’s Palawa people prefer? In the 2016 dialogue meeting leading up to Uluru, 100 Aboriginals at Nipaluna/Hobart rejected the voice model and opted for treaty.

The only way the Albanese government will advance a treaty is if a referendum is abandoned. A referendum is not needed anyway: the advisory voice can be legislated at any time. Putting the ‘voice’ in the Constitution does not make it permanent. One parliament cannot bind another under the parliamentary sovereignty rule. The solution is to abandon a risky referendum and simply legislate for both the voice and a treaty before 2025.

Aboriginal people are looking for, and need, real not symbolic change. Our culture, our history and our youth are assets capable of sustaining a healthy and vibrant Aboriginal future – if only some of what we once had is given back to us. We cannot rebuild our community without land and resources. We should share the country, share the decision making and resources. Symbolism and assimilation are outdated strategies. The voice model reintroduces those outmoded ideologies.

The one-sided airplay given to the voice supporters gives the false impression most Aborigines support voice over treaty. By comparing the voice idea with a treaty, it is plain why most Aborigines in fact prefer treaty.

Where the voice is advisory only, a treaty delivers a practical bundle of rights that can resurrect Aboriginal pride of place. Being a creature of the federal parliament, the influence of the voice is limited to Canberra. A treaty, however, is Australia-wide – it binds state, territory and federal governments, courts, police, business and the public. This is because a national treaty is given the force of a federal law.

The voice model cannot return land, will not deliver services, raise revenue or distribute money; it can only comment on federal political matters. The voice cannot pass laws or prevent laws from being made, or even save itself should a future government decide to dump it. Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney has repeatedly said the voice would not have a veto.

If Tony McAvoy’s NT Treaty Commission Final report delivered in June 2022 is a template, a national treaty can return crown lands without going through native title processes; provide a guaranteed source of revenue, establish a national indigenous body to prioritise needs and distribute resources.

Treaty might include six designated seats for Aboriginals. Each state has 12 senators, regardless of population (Tasmania has a population of 500m000 compared to NSW’s 8 million, but elect the same number of senators). A treaty might allocate one of the 12 senator seats for an elected Aboriginal. The result would give six Aboriginals able to vote against laws. Not perfect, but more effective than advising from outside the parliament.

For discrete Aboriginal communities, a treaty can give responsibility over land use and planning (not just collecting rubbish); education (including use of languages in schools), health, housing, and child protection; law and order and policing (including customary law where appropriate), and raise revenue from commercial use of Aboriginal lands.

Despite voice supporters charging that anyone who opposes the voice referendum is either ill-informed or racist, declining support for the referendum is a legitimate expression of free speech.

We cannot condone the personal attacks on Northern Territory Senator Jacinta Price or the Nationals’ David Littleproud.

We encourage Tasmanians to speak freely for or against the referendum. Support for a legislated treaty and a legislated voice, but No to a referendum, is a vote for Aboriginal people.

Money set aside for a referendum could be used more wisely

By Heather Sculthorpe

I would much prefer Prime Minister Albanese to back down from his resolve to have a referendum about The Voice than to argue for a No vote.

I do not like being on the same side in this debate as Warren Mundine and Jacinta Price. But I didn’t like being on the same side as Andrew Bolt in the “debate” about Bruce Pascoe wrongly claiming Palawa heritage. It’s the content that matters, not the politics of those with whom I agree on particular issues.

I do not support a referendum on The Voice because there are no compelling reasons in its favour, because it’s very expensive and the money would be put to better use elsewhere, because it will not improve the economic or social circumstances of Aboriginal people, because there are much quicker and cheaper ways of achieving the benefits claimed for it, and there are much more effective ways of enabling Aborigines to have a say in decisions that affect us – and even of giving effect to Aboriginal self-determination or recognising Aboriginal sovereignty.

Much of the recent attention to this question has concentrated on the form a national Aboriginal representative body should take. This is what the Marcia Langton and Tom Calma report was about (Indigenous Voice Co-design Process Final Report to the Australian Government, July 2021).

But this does not seem to be what a Voice referendum would be about. Whatever the referendum question ends up being, it could only be a simple question such as: “Do you support an Aboriginal Voice to Parliament in the Australian Constitution?” It would then depend on an Act of the Australian Parliament to provide the details of that Voice.

So why have a referendum at all, rather than going ahead now to legislate for an Aboriginal representative body? The pro-referendum lobby says it is only a change to the Australian Constitution, brought about by a referendum, that will prevent governments abolishing Aboriginal bodies, like the Howard government (supported by the Labor Party) abolished the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission in 2004. That argument does not stand up; the Constitution can enable a body to be formed, but it cannot command any government to pass legislation to establish such a body.

The lack of detail in the current referendum proposal about how a Voice would operate makes it clear that it is a concept with the same symbolic value as “Recognise”. Recognise was the catch-cry of the well-funded national group campaigning for Aboriginal people to be recognised in the Australian Constitution. It was established in 2012 by Reconciliation Australia and was opposed by most in the Aboriginal community in Lutruwita/Tasmania because it conferred no rights and was merely a statement of the very obvious: that Aboriginal people were on this continent since time immemorial, and certainly before the English invasion of 1788. It was a feel-good statement of no benefit to Aboriginal people, even though the Tasmanian Parliament made it part of the Constitution of Tasmania in 2016. Eventually federal funding stopped in 2017 – and then The Voice campaign began with large amounts of federal funding, and insignificant sums for other proposals such as Treaty, Truth Telling and Aboriginal seats in parliament.

The Recognise movement has already suffered an electoral defeat. The 1999 referendum proposed a change to add a preamble to the Constitution; the question was defeated in every state and territory.

The Tasmanian Greens received support of the major parties for their proposed change to the Tasmanian Constitution Act in 2016, and that amendment was passed by the parliament. The addition of an “Aboriginal recognition” statement in the preamble to the Tasmanian Constitution has made absolutely no difference to the power imbalance between Aborigines and others in Lutruwita/Tasmania, has given no extra advisory or decision-making power to the Aboriginal community, and has not improved the socio-economic circumstances of the Aboriginal community.

The consequences of a failed referendum are not hard to imagine. It would add to the public perception that “nothing works” and no alternative measure would be likely to find favour with government or political parties aspiring to government.

And it would inevitably bolster the campaign opposing the making of a Treaty with the Aboriginal people.

Political parties depend on popularity with the public to be elected to office, and no political party would support the making of Treaty that recognises Aboriginal rights when the public has just rejected a proposal for a Voice, which confers none.

The Voice proposal is undoubtedly about advising and not about deciding. As such it does not add much to what already exists, but would come at considerable cost at a time when the economic and social position of Aboriginal people is declining.

There are still Aboriginal communities in Australia living in third-world conditions, with inadequate housing and lack of basic sanitation. A clear need exists that could achieve immediate results with the expenditure of the millions dedicated to a referendum in the Albanese federal budget.

Tasmania needs to do its own truth-telling

By Maggie Walter

In 2017, more than 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander delegates met at Uluru. I was honoured to be a member of the Tasmanian contigent. The outcome was an open letter to non-Indigenous Australia: The Uluru Statement from the Heart, proposing a way towards a fair, just and truthful relationship between the continent’s First Peoples and those who arrived during and after colonization. In short, truth, treaty and voice.

These elements are distinctive but interlinked. There can be no valid voice without treaty and not treaty without truth. And while the Uluru Statement sets a national ambition, Lutruwita must do its own truth-telling.

The founding truth of this state is colonisation, a deliberate and formally sanctioned taking of the land. Under Terra Nullius, Palawa were made to legally disappear. Such declarations did not make our people actually disappear. That job was done by hand: through war; violence; martial law; forcible removal and relocation; abduction; rape; taking of children; imported diseases, mistreatment and duplicity. That is the truth.

Some of this is recorded in the many books written about the near genocide of Palawa. But many books do not equal a telling of truth. We know a lot about a little. Full truth-telling is weighed down by 200-plus years of silence and a fondness for the comfort such silence provides.

Saying the truth is largely untold is not saying that the truth is unknown, or unknowable. It is there in the archives, in the reports of colonial authorities, in the records of day-to-day operations of the colony.

And history is personal in Lutruwita. There is no written Palawa record, but our families know the truths of the abduction, rape, enslavement and frequent murder of our matriarchs and the systemic taking of our children.

Colonisation did not end with Truganini. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Palawa survivors were systemically shamed and discrimated against while also having their existence officially denied. That is the truth.

The Uluru Statement is clear in its connection of the past with the present, stating: “Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are alienated from their families at unprecendented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them.”

The 2022 Closing the Gap Information Repository reveals that in Tasmania, Aboriginal men are more than five times as likely to be imprisoned as non-Aboriginal men. For Aboriginal women the rate is nearly 10 times as likely. And Aboriginal children are more than five times as likely to be in out-of-home care.

So, what could truth-telling in Lutruwita look like? Here I draw on my 18 months with the Victorian Yoorrook Justice Commission. Yoorrook is a Royal commission and the first truth-telling body in Australia. Its mandate is to establish the truth of Victorian First Peoples’ experience of systemic injustices since 1788. Yoorrook is now heavily engaged in this remit. More information can be found at https://yoorrookjusticecommission.org.au/

Can the Yoorrook framework be translated to Tasmania? Yes, but with caveats. Over the past decade Victoria has developed an infrastructure that includes Aboriginal public service leadership; the Advancing the Treaty Process with Aboriginal Victorians Act (2018); an elected representative body, the First Peoples Assembly of Victoria; and a formalized Treaty Negotiation Framework between the First Peoples Assembly and the state. All were achieved with bipartisan support.

None of this yet exists in Tasmania. All other states are further along their journey. Truth-telling and treaty-making can, and need to, run in tandem. To begin, we need to quickly establish a Palawa-framed and -led prerequisite architecture. I recommend the creation of a Tasmanian Office of Truth and Treaty Advancement as a first step. This office would be responsible for the collaborative high-level planning and design, inclusive of the Truth-Telling commission’s terms of reference. It would also be tasked with bringing Palawa together.

The state’s primary role is to fund this office and deliver the enabling legislation. Only then can a Truth-Telling Commission be established.

The Royal Commission model works. Palawa need to trust the commission to tell their truths. Non-Aboriginal Tasmanians need to trust in the evidence for those truths. Something lesser is a waste of everybody’s time.

So, do we, as a state, have the courage to begin this necessary formal, public reckoning with the truth of colonisation? The future of our island home is at stake.

Published in The Mercury, Saturday, 21 January 2023